Climbing Mount Zeil ( Urlatherrke)

Elevation: 1,531 metres Nearest town. Alice Springs

Difficulty: Hard Date[s] climbed: 24 Sept, 2009 Location: N.T. Author: Graeme

Mount Zeil

is located at the western end of the MacDonnell Range in the Northern

Territory and is very remote. It is the highest mountain west of the Great

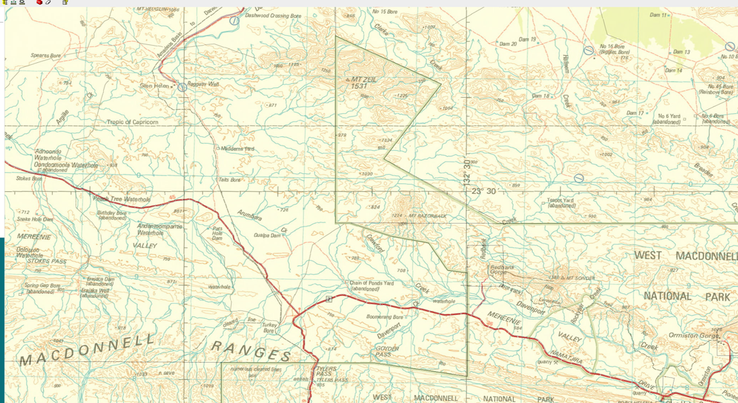

Dividing Range. In 2009, after much research and contact with Chris Day (the N

T chief district ranger), we decided to make our attempt from the NW end, via

Glen Helen station and the Dashwood Bore. Approval was required to cross Glen Helen,

although there are no gates. In 2020, Glen Helen, and the adjacent Narwietooma and

Derwent Stations were purchased by “Hale River Holdings”, and approvals

may be needed to cross.

(The previous owners of Narwietooma Station

kept a small holding at the base of Mt. Zeil, including

an airstrip, and have recently opened the Mt Zeil Wilderness Park, with the aim of allowing people

a feeling of staying in the remote outback, along with access to climb Mt. Zeil. This is now an alternative and attractive option to our route)

Warnings

Mount Zeil is

in an extremely remote and inhospitable area. The climb is long and can be dangerous

as there is no track to follow and the rock base is loose. You will spend ten

hours at the best, trying to keep upright as the mountain moves under you. The

spinifex is horrendous, but after a couple of hours trying to maintain a

footing on the loose surface, stepping on the edges of the spinifex seems to at

least guarantee some purchase underfoot, notwithstanding getting spiked. After

a while, you forget the spikes.

There is no water anywhere on the mountain, and

temperatures, even in the cooler months will possibly reach 35 degrees. In

desert regions, it is recommended that you drink 1 litre of water per hour of

exertion, but 10 litres equals 10 kilograms and you will not want to carry that

amount considering the added weight of emergency kit, satellite phone, lunch,

snacks, and layers of clothing including a jacket. We took 5 litres each, and a

couple of energy drinks, and ended up low on water and severely dehydrated.

Only well prepared and experienced climbers should attempt this climb. It can

be done in one long day, as we did, but it’s probably safer to camp and climb.

Take a satellite phone and don’t try this one solo. Medivac support if needed

will likely have to come from Alice Springs, and travel insurance should be seriously

considered.

History

Mount Zeil has

an interesting and elusive history. The indigenous people named it

“Urlatherrke”, after the

Yeperenye caterpillar. However, the correct naming of Mount Zeil is still

controversial and subject to ongoing resolution. The name Zeil

was first used in a footnote in Ernest Giles “Geographic Travels in Central

Australia, Page 68”. The footnote, written by Baron Ferdinand von Mueller

states:

“On

reference to the accompanying map

it will be observed, that one of the culminating points in the

MacDonnell Range, discovered during this expedition, was named Mount Sonder, in

honour of Dr Will. Otto Sonder of Hamburg, who largely elucidated the marine algae

of Australia, and who also much contributed towards the knowledge of the land

plants, particularly of the South-western portion of our continent. Two other

high mountains in the same range were dedicated to Count Zeil and Baron von

Heuglin, who distinguished themselves by recent geographic explorations in

Spitzbergen, the latter also by his extensive zoologic researches in North

Africa - F.v.M.”

It seems that Baron von Mueller

gave the names to Mount Zeil, Mount Sonder and Mount Heuglin at that time. In a

letter to Sir Henry Ayres, the South Australian chief secretary, von Mueller discusses

Giles expedition and states:

“some of the new mountains, and one of the

watercourses remained unnamed, the new geographic appellations to be chosen by

the South Australian authorities.”

The printed

maps in “Geographic Travels in Central Australia” show Mt Sonder, Mt Zeil, Mt Heuglin,

and Haasts Bluff, with the Finke River originating between Mt Sonder and Mt

Zeil where today Redbank gorge sits. However, on map PL 2902/1 published by the

Adelaide Surveyor Generals office in 1876 [based on Giles], only Mt Sonder is

shown. It is interesting on reading Giles original journal, that he was unable

to penetrate the South MacDonnell Range, being turned westward by a flooded

gorge (seemingly south of where Glen Helen gorge is today). He climbed a nearby

hill, “And could

see to the North was the main chain, composed for the most of high mounts…”

So, Giles, who was an explorer

and not a surveyor, did not go anywhere near where Mount Zeil stands today!

If

he saw it at all, it would have been as an indistinct high point above what is

today Mt. Razorback. The name Mount Zeil was given to one of the “high mounts”

next to Mt Sonder and the Redbank creek, in the position where Mt Razorback

stands today. Mt Heuglin was further to the west. Tietkens, who

accompanied Giles on his second expedition, went back to the MacDonnell’s in

his expedition of

1889 (Journal of the Central Australian Exploring Expedition, 1889). By this

stage, he was a qualified

surveyor, and so his bearings are far more reliable than Giles. He climbed, “Mt Razorback”

on April 2nd 1889 and took readings to Zeil” (of Giles) and “Sender” (Sonder)

His Zeil reading

is strange, but “Sender” is spot on. Then on April 4th, he ascended Mt. Sonder

and took readings to Mt. Razorback, Mt. Zeil, and Haasts Bluff. These readings

correlate well with the established positions

of these mountains today. But Mt Heuglin has disappeared. To totally confuse

the scene, in 1894, the Horn expedition went through the area. The Horn expedition

was an interesting concept, as command had been set up as a democracy, with no leader

and decisions to be made by consensus. However, Chas Winnecke was entrusted

with the safety of the expedition. Winnecke was a surveyor and geologist, and

pedantic with his readings. On Monday June 25 1894, he took bearings from a

waterhole named “Andantompantie”.

“From here

Mt Heuglin bears 51 Deg 50’ distant fourteen and a half miles, Mount Zeil 86 Deg

30’ distant 15 miles, and Mount Sonder 93 Deg 30’ distant twenty-four miles. The

former two mountains

have been transposed on several charts, and Mount Zeil has been locally renamed Mount

Razorback; I cannot, however, adopt these erroneous alterations.”

The question

is, what were the alterations based upon? Winnecke must have had latitude and longitude

positions, and previous bearings for Mt. Zeil and Mt. Heuglin, but these seem

lost in time. On page 46 of

his journal, he states:

“Computed

the altitude of various mountains……… I have

properly rearranged the names of several hills, expunged the name of Mt

Razorback, which is

Giles Mount Zeil, and dedicated the high mountain west of Mount Heuglin,

visited by me in 1879,

Mount Chewings.”

There seems no

doubt, the original Mount Zeil (of Giles), was where Mt Razorback is today. Today’s Mount

Zeil was originally named Mt. Heuglin, and Heuglin was Mount Chewings. Somehow,

Winnecke’s changes were not taken up; Mount Heuglin became Mount Zeil, and poor Mr. Chewings

lost his mountain. However, a range, the Chewings Range, was named after him. The names of

Mount Zeil and Mount Heuglin were only gazetted on 5/8/1959 (NTG34), as was Mt. Giles. In 1956,

Pastor P. A. Scherer of Hermannsburg mission wrote to the Director of National Mapping,

Canberra, “with information on a number of central Australian features”. (The mountains in question)

I have

attempted to find copies of Scherer’s letters, but there appears to be a

reluctance to release the

information. Correspondence obviously occurred, and Mt. Zeil was subsequently

gazetted in 1959. Any help would be appreciated in finding this lost detail. So, in summary,

a Mount Zeil was named (probably by Baron von Mueller after Giles 1872 expedition), but

it was in the position now named Mount Razorback. Mount Zeil’s name was only confirmed in

its present position after it was gazetted in 1959, and Mount Heuglin moved (and reduced in

prominence and importance), to its present position. Mountains seem to move (see history of Mount Kosciuszko and Mount Townsend)

But I know we

climbed the highest mountain…… which was the objective all along.

The

Climb

Zeil is to be

my first of the State 8 . Brian has asked my son Sam to accompany him,

his wife Tanya, and Son

Kadison on a trip to climb Mount Woodroffe in South Australia. Sam and Kad are great friends,

but obviously my wife Cate and I are intrigued as to what this is all about.

A mountain? and

in Central Australia. What could possibly go wrong….? So, we begin the

discussion, and I am introduced to the State 8 . Brian has already

climbed a couple, and during the discussions,

Cate and I decide we might go along for the trip to Woodroffe. Brian has a

brilliant business past, and somehow managed diplomatically to bend the trip

details as, “there is a small mountain in the Northern Territory named Zeil

that is part of this thing called the State 8 and just perhaps the two of us

could do this first”.

We will then

meet Cate, Tanya, Kad and Sam at Uluru, where we will start our Mt. Woodroffe

trip. So, the planning began. Brian had already researched Zeil extensively and

I credit him with all the planning and route decisions. However, Zeil is not a

mountain to undertake solo… and it is certain that some faith in your climbing

partner is required. But it turns out that Brian is a risk taker, and our

journey toward the State 8 (and without knowing it at the time, the State

16) begins.

The plan is

for Brian and I to fly to Alice Springs where we will be based for two nights

and then drive to

Uluru to meet Cate, Tanya, Kad and Sam. Zeil’s defences are working overtime,

as the biggest

dust storm to hit Sydney in a century closes Sydney airport for 4 hours and

delays our flight to

Alice Springs. We finally depart and collect our 4WD late in the day, but with

enough time to pick up

some necessary supplies, including food for the climb, lots of water, and the essential satellite phone for safety. An early night, as we hope to climb Zeil the next

day.

Our chosen

route to Zeil is via the Tanami Road, left onto Kintore Road and then hopefully somehow find

the turn through Glen Helen station to the Dashwood bore. We leave Alice Springs around 3 AM,

anticipating the distance to be around 220 km, hoping to be at the Dashwood

turn at dawn as we knew we would need daylight to find our way from there. As

Brian has researched the route, he acts as navigator on the way out as I drive.

This sharing of duties proves fortuitous (at least for me). We have no problems

finding the way, although we are delayed considerably by having to avoid

seemingly endless Kangaroos en route. Finally, we turn onto the Dashwood turn, and

stop to take early light pictures. If you go in this way, make sure you note

your entrance to the Dashwood, as on return, it is almost impossible to find. ( First

mistake, more later)

Across the

Dashwood at the bore and across scrubby plains and we are at the base of Zeil.

We are both keen to begin the climb and so drive as close as possible to where

we have planned to start (plots on Google Earth mainly) We park the 4WD in the shade of a large tree ( mistake

number 2) and decide on equipment and supplies to take. Brian carries the

Sat phone, but boy my pack feels heavy. Four litres of water each and a couple of “Up

and Go’s” should do… ( mistake number 3) . So, the climb begins.

You cannot see

the summit of Zeil from the western end, and in fact you have to partially

climb the mountain 4

times, as each false summit takes you higher, but then you need to descend

partially before the next

“up”. So, we rely on compass and GPS bearings to start the route. We decide to climb high

initially, hoping to see the route ahead. This leads to us climbing too far to

the west, and having to

descend considerably before starting up to the next false summit. The crumbling

rock and huge

spinifex warn you of the ordeal ahead, but each summit leads to new hope. “We

must be close to the

top” I tell Brian at least 3 times, but after 3 hours of climbing and dodging

spinifex, the real summit

shows itself ever so high over the distant horizon, at least 2 hours away. This

is the first climb of

my attempt at the State 8 , and I look at Brian, slightly appalled. What

have I got into? I think

fleetingly. Brian however, is looking up at the mountain with a steely stare as

if to say, “bring it on”.

We continue.

The climb is long and hard in 35-degree heat, and I know we are both feeling

the effort when

Brian decides to show me how to use the satellite phone, “in case I don’t make

it and you have to

ring” … ( mistake 4) To our amazement we find small Cycad palms, and then

a last steep scramble to the top. We have made it, and the view makes it all more

than worthwhile. On the summit

is a cairn, with a book to commemorate climbers. It also has a note from the helicopter

pilot who flies to the summit to service some electrical equipment there. In

his opinion, we (the

climbers) are crazy!!! Book signed, and Brian cranks up the Sat phone and we

speak to Tanya and Cate,

euphoric that we have achieved the first part of our plan. Lunch on the summit; in one

of Australia’s, if not the worlds, more isolated places! The “Up and Go” tastes wonderful, and

then time constraints mean it is time to descend.

On the climb

up, we aimed high and tried to stick to the ridge tops, although this meant

wasting altitude as we

climbed false summit after false summit. On the way down, we decide to be

clever and skirt

around some of the tops. This proves to be mistake number 5, as walking across steep

slopes with crumbling rock and huge spinifex is a nightmare. The heat has become

appalling. We have rationed water

on the climb up to two litres, but by this stage we are dehydrated, overheating

and struggling with leg cramps. There is no

shade of any kind on the mountain and although we are both still moving well,

we decide to

descend an earlier gully to the West, in order to miss a couple of false

summits, and to reach the base

earlier. Coming down turns out to be as hard or harder than climbing up, as the rock lets go

under any pressure, and the descent turns into a battle to stay upright. Half

way down we drop

into and follow a steep, dry creek bed and find the first shade we have seen all day,

both feeling the effects of the heat and the pummelling our legs have taken on

the descent. I think of early explorers, who failed to survive this harsh

environment, and have a better understanding why.

After a short rest sitting in

a rare, putrid, shallow water hole, splashing the gross liquid on our faces to

assuage the heat, Brian asks whether I can get up, and I have to consider the

answer. But we do.

That test

passed, we finally reach the base, and a theoretically short 5 km around to the

car. I have little water left, and the more experienced Brian a little more, but

we have litres in the 4WD. Now where is this car? We have cleverly parked it under

a tree, and now, tired and dehydrated after a ten hour climb, with evening

falling rapidly, we can’t find it! (S ee mistake number 2) Eventually Brian realises we can track it on the GPS, and I independently find the tyre

tracks we made on the way in. In the failing light Brian’s gaze is glued to the

diminutive screen of the GPS and he stumbles into a hidden stump hole and gashes

his leg. Zeil continues to punish us. And finally, the car appears, a quite

emotive moment. Our stored food and water feel like lifesavers, and possibly

are. As I had driven

out, it is Brian's turn to drive home. This is fortunate, as my legs are

cramping badly, and we would probably have been in first gear all the way home

if I had to drive.

So, we begin

our return without a glance back at our nemesis; it is now nearly dark, however

when leaving Zeil, the landmarks are not as obvious as when coming in. (like a

huge mountain to aim at). We drive through creeks and an occasional tree or two;

Brian has noticed my glanced alarm at our skirmish with the trees, but we are desperate

to get back to familiar territory. We finally find the Dashwood bore. On

crossing the Dashwood there is no track visible on the other side and we spend

a frustrating and increasingly alarming hour driving in circles and hitting

dead ends, trying to find it. Finally, we

follow what appears to be a track going in the correct direction, and we are

back on the route to Alice Springs. Brian describes it as one of the hardest drives he

has had to do, but he gets us back to the motel around midnight. A 21-hour

round trip! We have done it, but as we departed, I think Zeil released an

acknowledging smile for the pain it has demanded as its due.

Apologies to

Chris at Yulara resort who received the full brunt of our wives’ anger when

they assumed that we

were “dead in a ditch” when we weren’t at the airport to meet them as arranged.

Mount Zeil is a

hard climb, and a potentially dangerous one. It can be done in one day, but it

would be far better to overnight and enjoy the isolation and the moment. Take plenty of

water as there is none to be found on the mountain, enjoy the challenge, because it will

test you.

Mount Zeil - Click on an image for full resolution

Climbing Mount Edward (Ulampawarru )

Elevation: 1,397 metres Nearest town: Papunya or Haasts Bluff

Difficulty: Hard Date[s] climbed: 27 July 2017 Location: N.T. Author: Brian

Mount Edward, the second highest mountain in the N.T. is located roughly halfway between Papunya to the north and Haasts Bluff to the south. It is the epitome of "remote" and virtually isolated from the climbing fraternity as it is located within the NT Central Land Council. The area is rugged, harsh and unforgiving, but grandly beautiful. Mount Edward is the gatekeeper to climbing the second 8; if we are unsuccessful then it will be pointless taking on the equally daunting Mt. Morris and Mt. Bellenden Ker.

Warnings

This is an extremely remote area; there is no local backup or support, and support if needed would likely have to come from Yulara or Alice Springs. There is no track on the mountain plus the geology is extremely rough and loose. You need to be a very experienced climber to attempt this climb. There is no water on Mt. Edward. The climb is fairly short and can be achieved in one day but it is very challenging. The track in from the Papunya end, if you can locate it, is barely navigable in a real 4WD and quite overgrown. Roads in the area can become impassable following rain. Access to the area must be obtained through the NT Central Land Council.

History

There is a paucity of information about Mt. Edward and no written record I can find of anybody ever climbing it. Notwithstanding, there is a very old, overgrown cairn at the summit, which attests to it having been climbed at some time in the past. (Graeme and I left a small memento of our climb at the base of the cairn) Mt. Edward is approximately 85 kilometres, (as the crow flies) northwest of Glen Helen Resort and is located within the Central Land Council, Western Region 5. Accordingly, access to this wild area is by permit only through the Central Land Council.

The first written report I can find of the existence of Mt. Edward is chronicled in the “Journal of The Horn Scientific Exploring Expedition 1894 – Charles Winnecke", which is a fascinating read.

The Belt Range is located halfway between the two aboriginal settlements of Papunya and Haasts Bluff at the western end of the West MacDonnell Ranges. It was first described by the Horn expedition on June 22nd, 1894. The Belt Range, named by Winnecke, was named after William Charles Belt, a prominent SA barrister. The Belt Range is comprised of three prominent peaks. These were named after Belt’s three sons, Edward, William and Francis.

“ The natives seem to have no particular name for these imposing geological features. Throughout the journey I have endeavored to obtain the aboriginal appellations for all objects seen but in this instance the words given by various natives are totally at variance and seem to be descriptive for the occasion only. I have therefore styled these three important mountains Mount Edward, Mount William and Mount Francis”. Winnecke 22-6-1894.

The Horn expedition occurred some 12 years after Ernest Giles first traversed the same area in 1972. At that time Giles discovered and named Haasts Bluff. Accordingly Mount Francis was incorrectly afforded its name and it is now formally known as Haasts Bluff or Ikuntji. Of course, this entire area has been well known to the local indigenous people for many thousands of years.

The view from the top of Mt. Edward is one of the most spectacular in Australia and it would be amazing to undertake a climb of the three Belt Range mountains in turn. A future challenge perhaps?

Planning

As mentioned, there is virtually no written information about climbing Mt. Edward. Given it is located well inside aboriginal land, like Mt. Woodroffe, access is extremely limited. After a lot of web surfing, planning for the trip was based on obtaining a permit from the CLC, poring over all manner of Google Earth views, spurious maps and organising transport and accommodation. I hasten to add the topography imagery presented on Google Earth is not representative of the actual area and it is infinitely more challenging than depicted. Take a wrong turn and you will end up in a dead-end ravine.

After months of research and peering at GE we decided on a route that saw us begin on the north side of Mt. Edward (The Belt Range runs East/West) and to climb south’ish up a series of ridges, over a false summit, a drop down, then up further ridges to the southwest. Our base camp was Glen Helen Resort, approximately 127k by road and bush tracks of varying quality, to the base of Mt. Edward. We debated whether to come in from Papunya or Haasts Bluff as there is a rough bush track connecting the two. After much discussion we decided to come south from Papunya. Given there is a longer but much better road connecting the two towns and our experience on the former, we doubt it is used often. As it turned out, the desk planned route we selected is possibly the only practical way to climb Mt. Edward. Perhaps we are getting smarter at planning but concede there was a huge element of luck involved.

The Climb

Winter 2017 and we fly into Alice Springs, pick up a Nissan Patrol hire car, purchase supplies and make our way to Glen Helen Resort, which is about 135 km west of the Alice. Described by Google Maps as a “2-star rustic retreat”, it is the only food and accommodation in the area, however it is charming in its own way and certainly has all the facilities one needs, including fuel. Located on the Finke River the local scenery is outstanding and it’s a great launching place for the many attractions in the area. Winter is high tourist season and the place is normally booked out. We settle in, have dinner and prepare ourselves and gear for the following days challenge.

Up at 3 am and we are kitted up, breakfasted, a last gear check and with Graeme at the wheel he heads the Patrol slowly west towards Papunya. Our emotional mix is a combination of climber’s excitement to be taking on this challenge but tempered with healthy trepidation given the many unknowns. Google Maps indicates it could take us 3 plus hours to get to Mt. Edward, hence the early start. Travelling in the dark is not recommended given the wildlife, mainly Roo’s, which we encountered in huge numbers when we climbed Zeil.

Thirty-six kilometres on bitumen with minimal wildlife, however it’s time to get into the real drive and we turn right onto the Namatjira Kintore Link Road. This road/track is typical of those encountered throughout the Centre. Well-formed and reasonably graded in general, but lots of corrugations. We travel comfortably and make good time but surprisingly we don’t encounter much wildlife. Seventy-six kilometres of this bone jarring track and we are approaching Papunya. Our spirits are high, but it is hard to accept that we are really on our way to Mt. Edward given all the challenges so far.

Our wonderful Google Maps shows the track connecting Papunya and Haasts Bluff, should be appearing any moment, on our left. There is no track! Perhaps we have missed it in the dark. We double back but with the same result. (Upon inspection on our return in daylight, it appears the track has been closed for some time as there is no obvious turn in point) We hang a left before Papunya and figure we may be able to double back and find the track further south. This is not looking good; we are rapidly driving onto someone’s property, literally past their bedroom, dogs are barking and we blast through into the gloom. Metres further along we encounter wild donkeys of all things.

It's a dead end and with great apprehension we return back past the house expecting at any moment we will be confronted by an irate inhabitant. This is definitely not looking good and the whole trip is suddenly at risk, however Graeme is blessed with uncanny spatial awareness, and we stumble across a rough track that appears out of the darkness. With customary Graeme confidence he swings right onto the track. It seems to be heading in the right direction and with our luck holding we breathe huge sighs of relief when we figure we could be on the correct track.

Eleven kilometres and we swing right onto what we believe will be the track which will take us to the base of Mt. Edward. What a shocker this track is; barely wide enough for one vehicle and we wince as foliage runs down the side of the car. We have about 4 km of this at a very low speed and it is still pitch dark. Off-roading at its best and worst. Where is the moon when you need it? After 4 km we figure we must be there and we pull up and await dawn.

The early rays of dawn appear in the east, on a crystal-clear morning and we peer into the distance and try to determine where we are. Elation; incredibly we are at the base of Mt. Edward. There is a rough weir on our right which corroborates the location. We decide to push on a further 500 odd metres to a more likely starting point, which should take us to our planned starting point.

What a beautiful spot; absolute isolation and we are presented with outback Australia at its best. A small mob of brumbies appears just to add to the moment. Also a few wild cattle. We park in a safe spot and ensure we can readily see the car on our descent, an error we made on Zeil, much to our detriment.

Gear checked, both GPS’s activated and we are on our way. No gradual warmup, we are immediately climbing up. Our start elevation, consistent with much of the Centre, is around 720 metres. We are heading for 1,397 metres. Our route is based on the traditional safe approach, up the ridges. We rapidly gain elevation and the ridges narrow with spectacular and dramatic fall-offs on both sides. From this elevation we can see the pitfalls of climbing up the wrong ridges to our left and right. We take it steady. Up 50 to 75 metres and we take short breathers. We are delighted to find that our calculated route is actually leading us to the first plateau. And then we are at check point 1, at 1,320 metres. I’ve named this place Encounter Ridge; the reason becoming obvious in a short while. From here we have to head east for about 750 metres, drop down about 80 metres and then head up the final ridges to the top.

The mantra is stick to the ridges and we head off to the east. Wow! Whilst we are still following a ridge, it is extremely rough going. As on the upward ridges, underfoot the surface is made up of small to medium rocks that have broken down over millions of years. Unstable and hard to walk on. Clearly our ridge and mountain were much higher in the distant past and we encounter the base rocks that are witness to the inexorable break down of their birth. The ridge is very uneven and it is tough going. Progress is slow.

Graeme is leading and abruptly he is on his knees. A huge rock, (the size of a small table) has expressed its displeasure when Graeme stands on it and it has roughly broken in half! Miraculously the two parts have fallen one way and Graeme has fallen the other. We are shocked; no injury at all but the outcome could have been much different. It could have been terminal or Graeme could have been trapped under the rock. It has shaken us up and soon after we decide to head straight down into the valley. (As it turns out the going at the bottom of the valley is fairly easy to traverse. (On our return we follow the valley and head straight up to the top of the ridge, a much easier route)

The way up from here is pretty obvious and we slowly progress up the ridges. No tracks on this mountain and every change of direction is unique. It’s very likely no human has ever trodden this particular path before. There is no wrong route however as all routes lead up. We push through low scrub and suddenly a ragged cairn appears. We have made it! We’re both euphoric and emotional. What we believed to be likely unachievable has been achieved. By two older bodied, but young in spirit, climbers. Our resolve, commitment, patience and bloody hard work, has been rewarded.

The handshake, only climbers understand, and then we take the obligatory pics, the smiles persistent on our faces. We have in our possession a special memento which we have encased in a zip lock bag. We deposit this at the base of the cairn, which has seen better days. We have no idea who erected it but it does contain a large steel bar which I suspect could only have got there via a chopper. The cairn is heavily overgrown and it is as if the mountain is trying to reject its presence. A great discovery is a flowering specimen of the Mountain Hakea, exclusive to the MacDonnell Ranges. It only appears on the highest ridges.

My GPS indicates 1,390 metres which is pretty close to the target. We have walked roughly 4.3 km which makes for a round trip of roughly 8.5km.

The views from this place are incredible. Far to the east is our old nemesis, Mount Zeil, standing proud, as is befitting its title of tallest mountain in the NT. Given the challenges of summiting we decide to head down to the valley where we eat our lunch. We have done it.

Our return is fairly tough; not by distance but because the rocks underfoot are sharp and unstable. Climbing up the ridges the way forward was fairly instinctive and stable, but as we descend Graeme keeps checking his GPS to ensure we don’t stray off the correct ridge. It would be diabolical as most side ridges lead to massive drop-offs. We are both tired and having to backtrack would be emotionally and physically painful. We can see the car in the distance but in spite of the one foot after the other approach, going down is very slow. My feet are really sore. (My feet are normally sound but six months later my toes were still splitting and bleeding) Graeme confides to me that he is also doing it tough.

We finally reach the car, exhausted and leg and foot sore, but jubilant. Not a lot of native wildlife in the area but we are delighted to suddenly encounter a number of Spinifex pigeons. A simple but lovely discovery. I’m the return driver and quite enjoy the track back which is truly off-roading 101. We soon encounter the track to Papunya and in daylight we simply follow it back, passing by the Papunya airport, a reminder that civilisation will confront us soon.

We skirt around Papunya and only see the town from a distance. It appears to be very dry and a harsh area to live. Papunya is the home of modern aboriginal art in Australia which we were unaware of at the time. We return the same way but stop to glare at a small mountain which is reputed to be the forthcoming home of a very large, LED lit, religious cross; an initiative of the locals and a NSW Central Coast photographer who just so happens to live near us. Hopefully it never sees dark of night!

Back to Glen Helen Resort and we make calls home to our very supportive wives. It is impossible to impart the full experience to them. It will always be unique to Graeme and me. A wander around Glen Helen, food, showers and bed. Mt. Edward has been a wonderful challenge. It has been a pleasure and a privilege to have climbed it with Graeme.

Having climbed Mt. Edward which was the watershed for the Second 8, we now have a steely resolve to knock over the last big two, Mt. Morris and Mt. Bellenden Ker.

Mount Edward - Click on an image for full resolution